March 23, 2009 -- Approximately 70 adults and students rallied at Bedford City Hall (Bedford, TX) to protest the juvenile daytime curfew ordinance. The day marked the six-month anniversary of the Bedford city council's decision to enact the curfew on September 23, 2008.

At the same time, nearly twenty miles away, another group of protesters rallied at the Dallas City Hall, to express their opposition to an expanded daytime curfew being proposed in Dallas. The rally came two days before the first of two public hearings in Dallas on the issue.

Many of the protesters at both rallies wore "Ditch the Daytime Curfew" shirts, and waved signs that read, "Ditch the Daytime Curfew" and "Fight Crime Not Freedom." Some people even made their own signs with messages like, "Public School Parent Against the Daytime Curfew."

The twin rallies generated media attention from well over a dozen media outlets, and served to thrust the issue into the national news (ex. Wall Street Journal) with the heated controversy over the issue in Dallas.

The rallies were shining examples of what can happen when communities of people come together to make their voices heard. Some might label these demonstrations as "rebelling against government," others, myself included, prefer to use the more accurate term: citizens participating in the democratic process.

As this political battle has escalated over the previous months, it has become more and more evident that reasoned and well-researched arguments are not enough to convince these councils that curfews are neither effective nor wanted by its citizens.

Officials in both Bedford and Dallas have completely disregarded the compelling facts that show that daytime curfews are not only duplicative (state truancy laws and criminal codes already exist) and unnecessary, but curfews do absolutely nothing to solve the juvenile crime problem or underlying issues related to truancy. In fact, curfews have been shown in study after study to actually exacerbate those problems.

Additionally, daytime curfews violate parental rights to direct the activities of their children. Curfews also stifle individual freedom, and can result in civil rights lawsuits against cities which implement them inappropriately.

"We’re against the government intrusion into parental rights to dictate the activities of our own kids and the punishment of a whole community of kids . . . in a misguided attempt to catch a couple of truants," said Anne Gebhart in a Star-Telegram article which came out the day of the rally.

The curfew criminalizes children just for being in public during daytime hours, even if no crime is being committed or suspected.

Bedford Mayor Jim Story told the Star-Telegram that he does not see the ordinance as a violation of civil liberties, and said that it has been effective in keeping students in school.

According to what truancy study and numbers are you referring, Mr. Mayor? And since when does the Constitution mandate that a certain segment of the population be presumed "guilty until proven innocent"? Does our Pledge of Allegiance proclaim "liberty and justice" for only those over the age of 16? The way I see it, a law with nearly a dozen "defenses to prosecution" seems a little weak in its attempt to pose as a fair and just law.

Mayor Story was also quoted in the article as saying, "We do not feel in any way that this ordinance harasses or targets anyone in any way... All indications show this is a very good ordinance."

Feelings are not facts, and "feeling" a certain way about something does not change the facts. The fact is, the potential certainly exists for the ordinance to be used to harass and target people. This has been shown in city after city where police officers, such as those in Houston, have used the ordinance to selectively target minority areas, or waited outside school buildings to issue tickets to kids arriving late to school.

There are many examples of police officers who have overstepped their bounds and abused their discretion to cite students who were outside during curfew hours for very legitimate reasons, even reasons protected by the first amendment. You don't have to look any further than Austin, Texas:

In March 2006, high school students hit the streets in Round Rock as part of a series of nationwide immigration protests. Over 200 kids were arrested for violating the city's daytime curfew. A federal lawsuit was filed on behalf of several parents and about 50 students who claimed the arrests were unlawful.

According to Jim Harrington of Texas Civil Rights Project, "A large number of them were charged for violating the youth curfew, even though the youth curfew has an exemption in it for First Amendment activities, and of course this is a classic First Amendment activity."

Did you get that? Even though there was an exemption in the curfew ordinance for First Amendment activities, that exemption was completely disregarded by police. Here's one of many articles about the story.

Bedford Mayor Jim Story told the Star-Telegram that "being home-schooled or out with parents does not violate the ordinance."

More accurately, those situations are actually considered defenses to prosecution, Mr. Mayor, which simply means that a police officer can use his discretion to issue a citation regardless. An otherwise innocent family would then have to go to court to try to prove their defense.

Never mind that fact that there are many legitimate reasons for a teenager to be out in public during school hours even without their parent, not the least of which may include a scenario where a homeschool child is finished with their school work, or a family decides to take a vacation and the child is outside playing, or a teen drives himself/herself to work. A public school child who is exempt from exams can also be the target of this ordinance. Any minor under 17 who is outside for any reason can be a potential target.

According to the article, "Gebhart said that the way the ordinance is written, police officers have discretion as to whether or not to issue a citation. It would be up to families to fight the issue in court, which could be more of a financial burden than the $500 fine issued with the citation."

Reasoned arguments don't seem to work. Pointing out constitutionality infringments does not seem to sway those in leadership. The message the councils seem to be sending us is: "Don't confuse us with the facts."

The lesson to be learned is this: Voters far outnumber elected officials. Voters should, therefore, use their voting power to inspire their leaders to action.

Campaigns like this are won at the grass-roots level. With numbers comes power. With power comes influence. With influence comes change.

The USA is not about government dictating to the people how it does things. The USA is all about citizens holding their government officials accountable and making sure those leaders observe and protect the rights established in the constitution.

In the historic words of John Paul Jones: We have not yet begun to fight!!

Let's continue to send that message loud and clear to our elected officials while we still have the liberty to do so.

Sunday, March 29, 2009

Monday, March 9, 2009

Watch Them Pull a Rabbit Out of Their Hat

On January 20, 2009, the HEB-ISD announced a decline in unexcused absences from 22,805 to 13,800: a difference of 9,005 fewer unexcused absences then those reported during same time period last year. The district attributed the change in unexcused absences to the juvenile daytime curfew ordinances in place in the cities of Bedford and Euless.

The school district's announcement came just five weeks after a December 16 work session with the Bedford City Council. At that time, the school district reported a decline of 2,600 unexcused absences since September 1, 2008, compared to the previous year. The ordinances in Bedford and Euless didn't get passed in either city until September 23, 2008.

A 40% improvement in just five weeks. Sounds impressive, doesn't it?

I find their figures intriguing as well, and I would be very interested to see the actual data that the district used to compile those figures, as well as the in-depth study that they conducted to specifically determine that the curfew was the reason for the decline in unexcused absences.

One problem I have with the district's figures and explanation of those figures is that school was not in session during two of the five weeks, due to Winter Break and the New Year Holiday which extended from December 22, 2008, through January 2, 2009.

When talking with the news reporter who wrote the article announcing the decline, he stated that the district's numbers were actually calculated through January 13, 2009. This would mean that the improvement happened in a period of just 10 days. For the sake of argument, however, we'll give the district those extra five days.

So, in just 15 school days, the school district reported that 6,405 (9,005 - 2,600) more students attended school during that period compared with the previous year.

Something up their sleeve? Well, the numbers certainly are suspect. And the district does not explain how it derived those figures. Another reason these numbers appear questionable is that all the public school students and parents with whom I, and many others, have spoken have heard nothing at all about the ordinance. I find that very curious, since the district is making claims that the curfew is working as a deterrent to keep kids in school. How can the curfew be working as a deterrent if no one knows the law exists?

Additionally, only two citations have been written since the ordinance went into effect. Only two. One curfew offender was caught in a fight and the other... well, all we know is that he spent 3 days in jail for some reason, and that must have been for something other than a curfew violation since those are considered Class C Misdemeanors and are non-jailable offenses. Seems to me like the criminal statutes already on the books would have sufficed for both of those cases, without the curfew ordinance.

On March 10, 2009, the HEB-ISD was invited to a second work session with the Bedford City Council. When a Bedford council member asked the school district for its truancy numbers, no one from the school district seemed to have those numbers available. The school district representative, an assistant superintendent for the district, stated that she didn't have that data, but indicated that one of the persons scheduled to speak on the council meeting agenda would have those figures.

Come on, now. If you're a school district attempting to prove that you have a truancy problem and trying to plead your case for needing a daytime curfew to handle the purported truancy problem, it seems only reasonable to assume that you're going to get asked the question "What are your truancy numbers?" at least once.

As it turned out, when the school district representative came up to speak as a "persons to be heard" during the council meeting and the council asked for truancy numbers, the speaker stated that he didn't have those numbers available.

What the numbers truly represent is shady at best. If the numbers represent school days and not individual students, then how many actual students are represented by that number? The district has not been forthright in explaining their numbers.

Maybe it's that new math.

It is disturbing that the public servants in our school system, who have the responsibility of educating our youth, can't seem to provide consistent and reliable figures on a matter that they proclaim is of dire importance and urgency.

The school district's desperate attempt to validate the need for the daytime curfew ordinance by directly attributing it to the huge increase in student attendance in such a short time frame is patently absurd. I would expect more from our education professionals.

It sounds like there really is nothing up their sleeve.

The school district's announcement came just five weeks after a December 16 work session with the Bedford City Council. At that time, the school district reported a decline of 2,600 unexcused absences since September 1, 2008, compared to the previous year. The ordinances in Bedford and Euless didn't get passed in either city until September 23, 2008.

A 40% improvement in just five weeks. Sounds impressive, doesn't it?

I find their figures intriguing as well, and I would be very interested to see the actual data that the district used to compile those figures, as well as the in-depth study that they conducted to specifically determine that the curfew was the reason for the decline in unexcused absences.

One problem I have with the district's figures and explanation of those figures is that school was not in session during two of the five weeks, due to Winter Break and the New Year Holiday which extended from December 22, 2008, through January 2, 2009.

When talking with the news reporter who wrote the article announcing the decline, he stated that the district's numbers were actually calculated through January 13, 2009. This would mean that the improvement happened in a period of just 10 days. For the sake of argument, however, we'll give the district those extra five days.

So, in just 15 school days, the school district reported that 6,405 (9,005 - 2,600) more students attended school during that period compared with the previous year.

Something up their sleeve? Well, the numbers certainly are suspect. And the district does not explain how it derived those figures. Another reason these numbers appear questionable is that all the public school students and parents with whom I, and many others, have spoken have heard nothing at all about the ordinance. I find that very curious, since the district is making claims that the curfew is working as a deterrent to keep kids in school. How can the curfew be working as a deterrent if no one knows the law exists?

Additionally, only two citations have been written since the ordinance went into effect. Only two. One curfew offender was caught in a fight and the other... well, all we know is that he spent 3 days in jail for some reason, and that must have been for something other than a curfew violation since those are considered Class C Misdemeanors and are non-jailable offenses. Seems to me like the criminal statutes already on the books would have sufficed for both of those cases, without the curfew ordinance.

On March 10, 2009, the HEB-ISD was invited to a second work session with the Bedford City Council. When a Bedford council member asked the school district for its truancy numbers, no one from the school district seemed to have those numbers available. The school district representative, an assistant superintendent for the district, stated that she didn't have that data, but indicated that one of the persons scheduled to speak on the council meeting agenda would have those figures.

Come on, now. If you're a school district attempting to prove that you have a truancy problem and trying to plead your case for needing a daytime curfew to handle the purported truancy problem, it seems only reasonable to assume that you're going to get asked the question "What are your truancy numbers?" at least once.

As it turned out, when the school district representative came up to speak as a "persons to be heard" during the council meeting and the council asked for truancy numbers, the speaker stated that he didn't have those numbers available.

What the numbers truly represent is shady at best. If the numbers represent school days and not individual students, then how many actual students are represented by that number? The district has not been forthright in explaining their numbers.

Maybe it's that new math.

It is disturbing that the public servants in our school system, who have the responsibility of educating our youth, can't seem to provide consistent and reliable figures on a matter that they proclaim is of dire importance and urgency.

The school district's desperate attempt to validate the need for the daytime curfew ordinance by directly attributing it to the huge increase in student attendance in such a short time frame is patently absurd. I would expect more from our education professionals.

It sounds like there really is nothing up their sleeve.

Labels:

attendance figures,

Bedford,

daytime curfew,

HEB-ISD

Friday, March 6, 2009

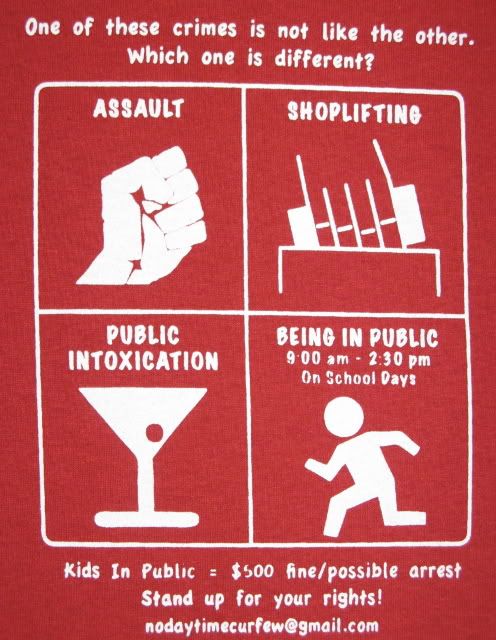

One of These Crimes is Not Like the Others

February 10, 2009 -- While researching various categories of crime in the Texas Penal Code in preparation for the February 10 Bedford city council meeting, I found myself humming a familiar tune from Sesame Street.

You are probably familiar with it, so feel free to sing along:

One of these crimes is not like the others.

Which one is different?

Do you know?

Can you tell me which crime is not like the others?

And I'll tell you if it is so!

Here are your choices:

• Public Intoxication

• Indecent Exposure

• Shoplifting (petty theft)

• Simple Assault

• Walking in public between 9am and 2:30pm on school days

Did any one of these stick out to you as being very unlike the others?

Did you know that all of these actions are actually the same offense under the law? These are all examples of Class C Misdemeanors. Criminal charges for which arrests can be made.

The juvenile daytime curfew makes being out in public EQUAL to:

public intoxication, indecent exposure, shoplifting/petty theft, simple assault, and a host of other crimes identified as Class C Misdemeanors in the Texas penal code.

Does something not seem quite right about that?

What I find interesting is that when I asked my kids to try to guess which of these crimes was different, even my 6 year old was immediately able to point out that walking in public was not like the other "bad things." In fact, he was puzzled as to how walking in public could be considered "bad" at all.

It doesn't take a college degree, years of academy training, or even professional experience to figure this out. Even the Sesame Street crowd can tell the difference between a real crime and a constitutional freedom.

Big Bird would be proud. So am I.

You are probably familiar with it, so feel free to sing along:

One of these crimes is not like the others.

Which one is different?

Do you know?

Can you tell me which crime is not like the others?

And I'll tell you if it is so!

Here are your choices:

• Public Intoxication

• Indecent Exposure

• Shoplifting (petty theft)

• Simple Assault

• Walking in public between 9am and 2:30pm on school days

Did any one of these stick out to you as being very unlike the others?

Did you know that all of these actions are actually the same offense under the law? These are all examples of Class C Misdemeanors. Criminal charges for which arrests can be made.

The juvenile daytime curfew makes being out in public EQUAL to:

public intoxication, indecent exposure, shoplifting/petty theft, simple assault, and a host of other crimes identified as Class C Misdemeanors in the Texas penal code.

Does something not seem quite right about that?

What I find interesting is that when I asked my kids to try to guess which of these crimes was different, even my 6 year old was immediately able to point out that walking in public was not like the other "bad things." In fact, he was puzzled as to how walking in public could be considered "bad" at all.

It doesn't take a college degree, years of academy training, or even professional experience to figure this out. Even the Sesame Street crowd can tell the difference between a real crime and a constitutional freedom.

Big Bird would be proud. So am I.

Labels:

Bedford,

Class C Misdemeanor,

Crime,

daytime curfew,

freedom,

HEB-ISD,

Sesame Street,

Texas Penal Code

Wednesday, March 4, 2009

Let's Pass a Law . . . Just in Case

So, is there a juvenile crime wave in Bedford that is driving the Council's determination to support a juvenile daytime curfew? That is a legitimate question, and one that might be on your mind about now.

The simple answer is no. The not-so-simple answer is also no.

Even Bedford Police Chief David Flory admitted this: "We don't have a huge problem of running across kids in the afternoon." (Star-Telegram, October 4, 2008.)

Why, then, would he and the Bedford City Council support a restrictive ordinance to handle a non-problem?

During a work session on December 16, 2008, the Bedford police chief stated that law enforcement officers already have the authority to stop anyone they want for any reason, with only reasonable suspicion. This is true, so why do they need the curfew?

Let's have a crash course in Law Enforcement 101.

According to a 1968 Supreme Court ruling (Terry vs. Ohio, 1968), police officers have the authority to stop anyone, including minors, if the officer has "reasonable suspicion"; that is, he reasonably believes, based on the circumstances, that a crime has been committed, is being committed, or soon will be committed. Such suspicion is not to be based on a mere hunch.

These "stops" (siezures of persons) are also known as "Terry Stops," Police officers must only establish "reasonable suspicion," to conduct these stops; this is a lesser standard of evidence than "probable cause," which is what is required for an officer to make an arrest.

During a "stop," the officer can either physically lay hands on an individual for the purpose of detaining him, or use a "show of authority" (through his look, demeanor, and display of authority) to cause an individual to submit, or at least acquiesce, to that show of authority; to cause the person to believe that he has been seized; to cause the person to feel compelled to cooperate; or to cause the person to feel unfree to leave.

By contrast, the juvenile daytime curfew ordinance makes the very act of being in public a crime. An officer only has to establish that 1) an individual looks young and 2) he is out in public. That is all the evidence needed for an officer to establish "probable cause" that a crime is being committed. No real crime has to be committed other than the crime of being outside of the house. Probable cause is the higher evidence standard necessary for a police officer to arrest an individual, conduct a personal or property search, or to obtain a warrant for arrest.

The Bedford daytime curfew states that "a minor commits an offense if the minor remains, walks, runs, idles, wanders, strolls, or aimlessly drives or rides about in or about a public place between 9:00 a.m. and 2:30 p.m. on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday or Friday."

However, a police officer already has the justification (without the curfew) to stop someone who exhibits any of the following behaviors:

1. Appears not to fit the time or place.

2. Matches the description on a "Wanted" flier.

3. Acts strangely, or is emotional, angry, fearful, or intoxicated.

4. Loitering, or looking for something.

5. Running away or engaging in furtive movements.

6. Present in a crime scene area.

7. Present in a high-crime area (not sufficient by itself or with loitering)

A minor out in public during school hours might fit the descriptions of 1, 3, 4, 5, or even 6 and 7 if their actions give a police officer reason to suspect that they might be involved in a criminal action.

The curfew, on the other hand, makes the very act of "being in public" suspicious behavior and adds several more broadly-interpreted descriptions that go above and beyond those 7 descriptions referenced above. The curfew gives police officers much more latitude to make a stop, even though there might not be any evidence at all to suggest that a crime is being committed, is about to be committed, or has been committed. Again, the "being in public" is the crime.

Because daytime curfew violators give police officers the ability to make a valid stop without any suspicion of an actual crime (being in public is the crime that validates the stop) an officer can also frisk that individual if any of the following situations exists:

1. Concern for the safety of the officer or of others.

2. Suspicion the suspect is armed and dangerous.

3. Suspicion the suspect is about to commit a crime where a weapon is commonly used.

4. Officer is alone and backup has not arrived.

5. Number of suspects and their physical size.

6. Behavior, emotional state, and/or look of suspects.

7. Suspect gave evasive answers during the initial stop.

8. Time of day and/or geographical surroundings (not sufficient by themselves to justify frisk).

To summarize, the daytime curfew is not needed for police to do their job in enforcing criminal statutes already on the books. What the curfew does is create a short-cut to probable cause, by allowing law enforcement officers to stop any young-looking person who is out in public during curfew hours, whether or not there is evidence or suspicion that an actual crime is being, has been, or will be committed.

Let's review.

First, the curfew is a short-cut to probable cause by making "being in public" a crime. The curfew specifies that a minor 17 and under who is out in public is in violation of the ordinance. Minors out in public are committing a crime, according to the curfew; so instead of having "reasonable suspicion" to believe that a crime may have been committed, or about to be committed, police can instead establish the higher level of proof necessary for an arrest: "probable cause that a crime has been committed"; the crime is being outside of the house.

Second, the curfew makes being "young-looking" and "in public" during curfew hours a crime. What does young look like? Can you tell a 17 year old when you see one? Businesses that sell alcohol and cigarettes have a difficult time with this; therefore, many have adopted the policy of asking for identification from anyone who appears "younger than 30." The curfew ordinance could impact those over 17 who have a youthful appearance, causing those individuals to be treated like criminals just for being out in public.

So, why does the Council and police chief support an ordinance which gives police broad powers to potentially harass any young-looking person out in public during curfew hours?

Part of the answer can be found in the last half of the the Bedford Police Chief's quote: "But this [daytime curfew ordinance] gives us a means to deal with kids when they are absent from school." To him, the curfew is "just another tool" to deal with kids out on the street during school hours.

But, wait. They don't need daytime curfews to "deal with kids when they are absent from school." You see, the HEB-ISD already has a way to combat truancy issues, and that is to aggressively enforce the compulsory attendance laws that are already in effect. Texas statutes give school districts everything they need to effectively enforce compulsory attendance laws; and what's more, these statutes incorporate due process so that the rights of all citizens, students and parents included, are protected.

In fact, in 2007, the Texas legislature made it even easier for police to help districts enforce the compulsory attendance statute by amending the Family Code, Section 52.01, Subsection (e) to allow law enforcement officers to return a truant child to his school (HB 2237 and HB 776). This change undermines the argument that daytime curfews are needed to give police the authority to stop children during school hours.

What's more, the HEB-ISD has roll books, and they take attendance each day school is in session. The district knows which kids are present and which are absent. This makes it very easy to specifically target children who are out playing hooky without infringing on the rights of so many other students who have a legitimate reason to be out in public, but who are not enrolled in the HEB-ISD or follow the school district's schedule.

The juvenile daytime curfew ordinance is too broad, does not specifically target children of compulsory attendance age, applies to anyone who looks young regardless of any other suspicious behavior, and criminalizes stepping out of the house.

It's just bad law. Certainly not one we want to have around just in case law enforcement decides it needs another tool.

The simple answer is no. The not-so-simple answer is also no.

Even Bedford Police Chief David Flory admitted this: "We don't have a huge problem of running across kids in the afternoon." (Star-Telegram, October 4, 2008.)

Why, then, would he and the Bedford City Council support a restrictive ordinance to handle a non-problem?

During a work session on December 16, 2008, the Bedford police chief stated that law enforcement officers already have the authority to stop anyone they want for any reason, with only reasonable suspicion. This is true, so why do they need the curfew?

Let's have a crash course in Law Enforcement 101.

According to a 1968 Supreme Court ruling (Terry vs. Ohio, 1968), police officers have the authority to stop anyone, including minors, if the officer has "reasonable suspicion"; that is, he reasonably believes, based on the circumstances, that a crime has been committed, is being committed, or soon will be committed. Such suspicion is not to be based on a mere hunch.

These "stops" (siezures of persons) are also known as "Terry Stops," Police officers must only establish "reasonable suspicion," to conduct these stops; this is a lesser standard of evidence than "probable cause," which is what is required for an officer to make an arrest.

During a "stop," the officer can either physically lay hands on an individual for the purpose of detaining him, or use a "show of authority" (through his look, demeanor, and display of authority) to cause an individual to submit, or at least acquiesce, to that show of authority; to cause the person to believe that he has been seized; to cause the person to feel compelled to cooperate; or to cause the person to feel unfree to leave.

By contrast, the juvenile daytime curfew ordinance makes the very act of being in public a crime. An officer only has to establish that 1) an individual looks young and 2) he is out in public. That is all the evidence needed for an officer to establish "probable cause" that a crime is being committed. No real crime has to be committed other than the crime of being outside of the house. Probable cause is the higher evidence standard necessary for a police officer to arrest an individual, conduct a personal or property search, or to obtain a warrant for arrest.

The Bedford daytime curfew states that "a minor commits an offense if the minor remains, walks, runs, idles, wanders, strolls, or aimlessly drives or rides about in or about a public place between 9:00 a.m. and 2:30 p.m. on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday or Friday."

However, a police officer already has the justification (without the curfew) to stop someone who exhibits any of the following behaviors:

1. Appears not to fit the time or place.

2. Matches the description on a "Wanted" flier.

3. Acts strangely, or is emotional, angry, fearful, or intoxicated.

4. Loitering, or looking for something.

5. Running away or engaging in furtive movements.

6. Present in a crime scene area.

7. Present in a high-crime area (not sufficient by itself or with loitering)

A minor out in public during school hours might fit the descriptions of 1, 3, 4, 5, or even 6 and 7 if their actions give a police officer reason to suspect that they might be involved in a criminal action.

The curfew, on the other hand, makes the very act of "being in public" suspicious behavior and adds several more broadly-interpreted descriptions that go above and beyond those 7 descriptions referenced above. The curfew gives police officers much more latitude to make a stop, even though there might not be any evidence at all to suggest that a crime is being committed, is about to be committed, or has been committed. Again, the "being in public" is the crime.

Because daytime curfew violators give police officers the ability to make a valid stop without any suspicion of an actual crime (being in public is the crime that validates the stop) an officer can also frisk that individual if any of the following situations exists:

1. Concern for the safety of the officer or of others.

2. Suspicion the suspect is armed and dangerous.

3. Suspicion the suspect is about to commit a crime where a weapon is commonly used.

4. Officer is alone and backup has not arrived.

5. Number of suspects and their physical size.

6. Behavior, emotional state, and/or look of suspects.

7. Suspect gave evasive answers during the initial stop.

8. Time of day and/or geographical surroundings (not sufficient by themselves to justify frisk).

To summarize, the daytime curfew is not needed for police to do their job in enforcing criminal statutes already on the books. What the curfew does is create a short-cut to probable cause, by allowing law enforcement officers to stop any young-looking person who is out in public during curfew hours, whether or not there is evidence or suspicion that an actual crime is being, has been, or will be committed.

Let's review.

First, the curfew is a short-cut to probable cause by making "being in public" a crime. The curfew specifies that a minor 17 and under who is out in public is in violation of the ordinance. Minors out in public are committing a crime, according to the curfew; so instead of having "reasonable suspicion" to believe that a crime may have been committed, or about to be committed, police can instead establish the higher level of proof necessary for an arrest: "probable cause that a crime has been committed"; the crime is being outside of the house.

Second, the curfew makes being "young-looking" and "in public" during curfew hours a crime. What does young look like? Can you tell a 17 year old when you see one? Businesses that sell alcohol and cigarettes have a difficult time with this; therefore, many have adopted the policy of asking for identification from anyone who appears "younger than 30." The curfew ordinance could impact those over 17 who have a youthful appearance, causing those individuals to be treated like criminals just for being out in public.

So, why does the Council and police chief support an ordinance which gives police broad powers to potentially harass any young-looking person out in public during curfew hours?

Part of the answer can be found in the last half of the the Bedford Police Chief's quote: "But this [daytime curfew ordinance] gives us a means to deal with kids when they are absent from school." To him, the curfew is "just another tool" to deal with kids out on the street during school hours.

But, wait. They don't need daytime curfews to "deal with kids when they are absent from school." You see, the HEB-ISD already has a way to combat truancy issues, and that is to aggressively enforce the compulsory attendance laws that are already in effect. Texas statutes give school districts everything they need to effectively enforce compulsory attendance laws; and what's more, these statutes incorporate due process so that the rights of all citizens, students and parents included, are protected.

In fact, in 2007, the Texas legislature made it even easier for police to help districts enforce the compulsory attendance statute by amending the Family Code, Section 52.01, Subsection (e) to allow law enforcement officers to return a truant child to his school (HB 2237 and HB 776). This change undermines the argument that daytime curfews are needed to give police the authority to stop children during school hours.

What's more, the HEB-ISD has roll books, and they take attendance each day school is in session. The district knows which kids are present and which are absent. This makes it very easy to specifically target children who are out playing hooky without infringing on the rights of so many other students who have a legitimate reason to be out in public, but who are not enrolled in the HEB-ISD or follow the school district's schedule.

The juvenile daytime curfew ordinance is too broad, does not specifically target children of compulsory attendance age, applies to anyone who looks young regardless of any other suspicious behavior, and criminalizes stepping out of the house.

It's just bad law. Certainly not one we want to have around just in case law enforcement decides it needs another tool.

Labels:

Bedford,

daytime curfew,

probable cause,

reasonable suspicion

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)